Journal 2

000229 - Ironstone and Coal

Ironstone and Coal, a large part of my life spent underground, by David Taylor, writer of the first part of this journal, dealing with my birth, my antecedents and my boyhood. As in my first writing I stated that I just intended wandering by memory to any particular episode as it came along. Probably the result will be a kind of jigsaw, leaving the reader to put sections together. If I write as I have in mind, the piecing together of the different meanderings should not be too difficult.

000678

God makes bees, bees make honey,

the fillers do the work, the machine-men get the money.

Here I must explain that machine men was the name given to Sam and his sons and several other family groups who controlled the big drilling machines and blasted down the stone ready for filling. In spite of the poem above I never heard any differences regarding wage questions. I believe, I have said before, Cleveland was always a contented community. We who are left still say with pride “we never went on strike over a hundred and fifty years".

The main haul after was the endless rope, as the attaching of tubs both full and empty was by means of a hook like a crooked finger under each tub, the hook could swivel completely round, therefore when to slow moving rope was lifted by hand and dropped in to the hook, which took a half right or half left turn (didn’t matter which) away went the tub, as a rule that rope ran all day through the twin like railway tunnel, empties going in-bye, full ‘uns going out-bye (pit expressions), used generally throughout the ‘North of England, both Iron and Coal. Going in that first morning at every forty yards (the fixed distance between the pillars of stone left standing) each opening to me showed the work of that continual rope way.

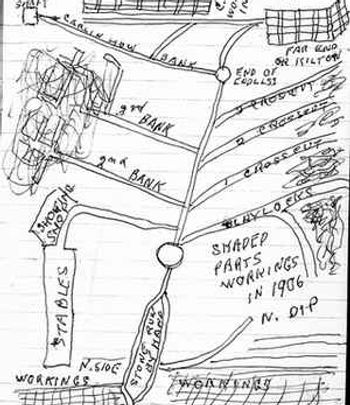

Clean and tidy and the tubs passing each other like robots, going where needed. I feel that to make clear to anyone uninitiated to mining tunnelling regarding the layout and planning of taking out stone and yet to leave some standing would be aided of a diagram about the matter. I have been down quite a few shafts (drifts are an entirely different matter, on which I shall dwell on my moving from Lumpsey to the Loftus mine with six drifts). On reaching the bottom of any shaft, great similarity to each other are the high white-washed brick arches going away usually North and South followed by more whitewash brick walling steel girders and roof steel supported eventually fading out to the walls and roof of the ironstone. On the following page (below) I have attempted a sketch which may be some use (I hope).

First Day down the mine

I ended up in book 1 telling Mister Chapman of my dilemma and the outcome. You will probably have noticed that I have underlined his full name above. This is with a definitive for any one who should read my story to know, that called very seldom adults and youths other than Sam or Sammy, I reverenced him to say, a great extent, that to me in speaking to or about him he was always Mister Chapman, the man who in nearly nineteen hundred and six, I followed onto Lumpsey Pit-top with two five pound cans of explosive (alternative gun-powder) slung over my shoulder, a little oil lamp in my hand, a bottle of cold tea in one pocket, my mid-shift-snack in the other. Into the cage and down, and then what seemed to me an unending journey, the three miles watching every step where to put my feet on the uneven surface till we arrived at the district of the pit, where I was to learn the heavy and laborious trade of Ironstone mining.

The part underground where we unloaded whatever we carried, hung our caps and coats up, no helmets in those days. Underneath Kilton Castle, where somewhere near, the miners had just joined up with those of Kilton Mine. There I was soon to learn that Sammy (I’ll drop the mister for ease) had a team, himself and three sons (stone getters) and twenty men to fill the stone. When I heard of this, it gave me the answer to a rhyme written on a large air door through which we passed out incoming journey – It read:

000679

Dip & Rise

When the sinkers had done their work and uncovered the seam, then the miners took over driving two headways, one North and one South. Headways is the name given in Iron and Coal and known to Edvass, actually the main tunnel at forty yards a road to the right and another to the left, spoken of as Stenton and every Edvass and Stenton number. At Forty yards away from the main tub road and parallel with another road was down called a travelling road, also along this, men, boys, and horses went to and from their daily toil.

It was while going along this travelling road that I saw through the Stensons (crossroads) the slow moving tubs. Notice boards were pretty plentiful stating that other than the people employed on the engine plant were forbidden to use it. And any accident occurring to trespassers was beyond the company’s liability. It was certainly a temptation, planks walked and well electrically lighted its whole three miles length. Certainly a big advantage than over the rough travelling road and our meagre lighting, horse drivers and leaders and other workers who moved about from one place to another during the shift, and the miners with a candle stuck in an old treacle tin or something similar, which was laid aside when they arrived at their various working places and hung up their caps. Coats and waistcoats and sometimes shirts, according to the temperature, which varies in different parts. Then the candle was stuck on the stone sides in a ball of clay.

Some fillers preferred to work in pairs (two to a place) usually the steady going non-stop type, some younger fillers keep for a better tonnage, working single. The fixed pay per ton filler in nineteen nought seven was five-pence point five eight farthing, slightly less than sixpence. A Lumpsey tub (wagon) could take up to two and a half tons, according to how it was filled, the men who preferred to fill a smaller number of more carefully filled and therefore heavier weighting tubs mixed the smaller pieces and shovellings to almost top level and then stacked large pieces along the sides and ends and then filling that in again as per the body of the tub. The height permitting for stone above tub level was eighteen inches, by the overman’s measure – elbow to finger end like a miniature haystack.

In our journey to work, that first morning I noticed we stepped over a light railway, a pair of rails on sleepers to the rise (in pit language, downhill is Dip and uphill is Rise) of Lumpsey mine going, as in my first day starting all left hand turns were steep rises, leading under ground to Brotton and the farthest left under the Churchyard and top-end of the village area. To the right were all dips going away from the endless railway. The first on the left, not the first from the pit bottom, led to the blacksmiths shoeing shop, enclosed between two large doors. A mile or so further in, on a busy hook crossing, full tubs on one set of rails emptied on another. We had to step over the couplings between tubs to get through. This road led to what was called (second Bank) a mile steady uphill to the district with miners, twenty two pairs (forty four) working and hand turning rachet machines for drilling the holes, charging and blasting and filling their own stone. A practice the men preferred, than to being a filler of stone for someone else’s getting. The big drilling machines and their teams of men and fillers didn’t last many years after my starting work. As these miners needed more timbering, the longer they worked, the large number of props (upright supports) being set and prevented the freedom needed to swing the rachet of the machine. So by the time I returned after the war in nineteen hundred and eighteen, all production was man power plus the hand ratchet. (I’m not sure whether that doesn’t need a ‘t’ in there 'ratchet' it does). Continuing our journey, about another mile on another double set of rails, again to the left and the rise. A clear crossing this time, but to our right ten or twelve full tubs waiting to be run around the tubs and on to the endless rope crossing I have just described, led away uphill again and occupied a rather bigger district and more miner’s. This was named ‘the third bank’. The fourth bank, some distance further on had a fence rail across the entrance with a ‘no road’, DANGER sign board attached. I will not go into details here but if time doesn’t run out on me I hope to write of some of the major troubles of Ironstone mining.

Now we have travelled past a left hand turn to the stables, past two left hand turns up the second and third banks, both working districts of working ratchet miners, past a derelict left hand fourth bank at present unfit for working, another five hundred or so yards and come to more or less a junction, white-washed stone and brick arches beautifully lighted, roofs steel girdered and lines running in many directions, noticeably the one going half left to the rise the road getting narrower and the light diminishing as far as we can see. This is Carlin How Bank.

The Carlin How miners descend a shaft only about two hundred feet deep and return that way but the fruits of their labour, the ironstone they fill, comes down that bank, joins in with the Lumpsey tubs, travels the same endless ropeway up the same shaft and to the same furnaces on Teesside.

000680

Tokens

Tokens for each filler or miner attending that morning, goes on a black board with numbers painted on it and below each number is a hook, on which hangs the tokens, small strong strings and the circular metal discs about ten-penny piece size, with the corresponding numbers to those on the board. One of these is attached to each tub filled, which when reaching the surface is removed from the tub by a boy, who calls out the number to the weighman in his office, who has already noted the weight of the tub and then adds the number of the token, which is now back on its own hook. A carefully checked weight list under glass on the pit top tells each man how many of his tubs have reached the surface and how much they weighed.

The Carlin How stone had journeyed about four and a half miles –from around Carlin how to somewhere near under Kilton Castle and woods, then back on its dead straight road to the Lumpsey Shaft. The Old Carlin How pit head stands below the village and not far from Skinningrove Railway Station.

The mile and a half or so of steel wire haulage rope, which served the Carlin How bank to and from Lumpsey, started from a drum in the engine house on the surface at Carlin How went down the side of the shaft, up and down which the miners used and then on its underground journey. The Carlin How shaft was also used for the lowering of long timber girders and railway metals so as not to hinder the continuous raising of stone, non-stop up the Lumpsey Shaft. Clock work is the only fitting word for that movement. Stone coming down the Carlin How Bank from the Kilton District, where I started work, from the second and third banks of which I have already spoken, from four districts on the dip side of the endless, from three districts on the alternative side of the shaft, of which I have yet to tell.

The endless rope never stopping (unless a break down), two haulage ropes drawing from the four districts on the low side and then joining in with those slowly moving along the main road. On the North side of the shaft, horses were used for taking the empties away from the pit bottom, whereas two very capable youths were employed, running trains of full tubs of stone from a large junction (we spoke of it as a siding) into which the horses took the empties, ten at a time, where they were shared out to the different districts.

In the running of the full tubs down the steady fall to the shaft, two well experienced youths could take up to fifty at a time. The tubs were joined by three link couplings when all were joined at the wheels of a few tubs which were sprigged so that they had to slide instead of running free. On the right I have attempted the sprag. Along the top edges of the train of stone the lads would have stuck quite a number of sprags, the cross piece of which is for hand protection, you could only carry about two by lugs (our name for the cross piece) thus the need for a few on the near side top of the tubs.

Click-Click ,Click-Click

The lad at the first tub would raise his lamp up and down, indicating that he was ready at the front. All prepared, the lad behind, swings his lamp back and forth sideways. All ready. The front lad clicks the sprags out of the wheels of the two front tubs and throws them on to the stone of the first tub for things to start to move fairly quickly, click-click, click-click, as the couplings tighten and more weight is added and more speed gathered, coming to the electric lights about a mile from the shaft, they set their oil lamps on a ledge at the side and give full attention to the running of the tubs. A non-stop run is what is needed or the whole procedure has to be repeated. Not too fast, not too slow, a sprag in here, a sprag out there, coming near the shaft, a sprag in the second wheel of the first, second, third and forth tub.

The lad at the back half releases all the wheels, runs forward with some sprags and helps the first lad halt the hundred and fifty ton train, with a slight bump into the full tubs standing there, throw all their sprags into an empty tub, sit inside it and wait of a horse coming to ride them back and start all over again. Have a woodbine, five penny (1/2p) now 'ha ha'. Thus with stone coming from eleven routes the cages up and down continuously, two full tubs running into the cage and bumping two empties out, made to me, a boy of fourteen, a real Kings Cross.

There is talks of the layout of the Lumpsey mine being mechanised and man handled, but the efficiency and timing were like clock work. A page ahead I have to make a sketch of all the working districts of the mine and in which direction they lay. The seam of the Ironstone throughout Cleveland went deeper the further one got from the coast, but after about six or eight miles changed to a steady rise by the time it reached the stemming carrier.

Yes, that is how I was described in those deputies reports in the early days, as one of the personnel for whom they were responsible. Stemming was the name given to small stones and stone dust used for stemming the explosive powder at the base of the ready machine drilled holes in the stone face to be blasted. My work was to gather off the floor into a strong wooden box with an iron carrying handle mix the small stone and stone dust well and pick out any stone too large for the one inch and a quarter powder pellets. For the purpose of this charging and shot firing (Sammy’s name in the deputy's book (Shot Firer). The gear used was a six foot wooden stemmer, very like a brush shaft swollen at the ends with a groove to slide back and forth in and out the drill hole sliding, groove resting on a slender six feet copper bronze rod, tapered to a point inserted into the powder. This rod was known as a pricker, then another stemmer, duplication of the wood one but of copper and bronze. Then wood stemmer was to push the powder to the rear of the drill hole then the pricker slid carefully along the bottom of the hole and pushed into the powder, then began the arm aching laborious task of stemming, me holding the heavy box of stone dust and bits, Sammy with the long copper stemmer in his right hand with its groove resting on the picker. Taking a handful at a time from the box, throwing it at that small middle and ramming it tight back to the powder. That right arm never stopped its rhythmic movement until the hole was completely filled to the entrance, various conditions made it necessary to require various amounts of holes being drilled in different places, as few as three or four to straighten up a working face or on a good straight face as many as fifteen or twenty for the one blasting. The position of the holes, in which turn to fire them, the depth of the hole, and the tangent at which it needed drilling, experience one could tell.

Drilling & Firing

I have overlooked another bit of equipment which could not have been done without. Another slender copper bronze rod again, six feet in length and called the scraper, one end of this rod was turned up, coal rake fashion, and in size about like the half of a ten-penny piece. This scraper was used first in preparing the hole for charging, the other end of the scraper had an eye like a needle, much larger of course, first, scrape out any dust left from drilling, next if the hole is damp, it is dried out by means of the eye end of the scraper with hay or dried weed, filling the eyehole and moved up and down until dry. Damp powder is a failure. Next the powder pushed steadily back with the wooden stemmer, then the pricker is slid steadily along the base of the hole and pushed into the powder, then the stemming with the copper stemmer until the hole is full. Then the pricker is carefully withdrawn and one hole is ready for the blasting. The method of detonating the powder in those times was by means of a squib (gun powder plot style) waxed paper containing powder at one end and a slow burning sulphur match of two and a half inches (three minutes burning time) made up the other half. A small piece of soft clay was laid on the end of the hole, the powdered end of the squib had to be bitten off, care taken not to spill the powder out. The squib laid gently on the doddle of clay, sulphur match protruding out from the hole, then pressed lightly into the clay. All tools, powder can, stemming box etc. were carried away round the nearest corner or crossroad and laid or leaned carefully aside. Then Sam took me some twenty five or thirty yards along and told me to stay there, allowing no one to pass until a number of explosions had taken place, shortly after Sammy came briskly down from the face, turned the alternative corner from where I was placed calling (Fire), he hardly seemed to get down and round to safety before bang went my first experience of an underground blast. The whole air and atmosphere shudders and Sammy called “ bring me a light David” the draught had blown his candle out and I was to learn later that when shot firing was taking place, naked lights over a large area were extinguished and re-lighted by means of the hand lamps with enclosed oil lighting carried by the horse drivers or leaders or lads like myself. In that first taste of obtaining iron ore, Sammy had fired the five holes he had told me to listen for. I was wondering what now, when he called “come on lad” I followed him along, head bent to keep below the thick, black, dense smoke, halfway down from the roof. He lit another candle from the tin on his belt and stuck it on a yard piece of old wooden stemmer “hold it up, follow me carefully and mind you don’t fall.” I soon found the warning to be necessary, for climbing higher on the fallen stone, which rocked and slid under ones feet, rather more than half way up to the roof which Sam was now touching with his hand, told me to hold the light right over to the left hand side and as he moved backward with a light iron bar tapping the roof, and occasionally with the sharp end dressing down loose pieces of stone or dogger roof, making it safe for when the fillers took over. He judged there was fifty to sixty tons of fallen mineral but there were two upper holes he could fire before we moved. Several lower holes could not be got to, until the stone was filled up. After charging and firing the two holes mentioned we moved a good ten minutes walk steadily downhill all the way to fire four holes already charged, but had had to be left just as, the ones we had left after just four places had been fired we went to the deputies cabin for our meal, a massive box with a hinged lid, holding saws, axes, light picks, for cutting baulk holes, a skilful job (more later), an ambulance chest, stretcher and blankets (which had to be taken to the surface to be aired every second or third day and always at noon on Saturday until Monday morning, every worker in the district got this little task in turn). After eats I saw for the first time the massive electric drilling machine at work, Sam’s two elder sons were actually controlling the drilling, while the youngest Ernest (two years my senior) stood at the outer end of the bogie, letting it run back a little or prising it ahead, when signalled by Fred, the drill changer. Speech was of no use, the din was terrific. Bert, the eldest son was stood on the front of the carriage and when Fred switched off, withdrew the drill from the hole, inserted a longer one, coupled it up to the drilling and Fred switched on again. I never at any time heard one of those young men speak while working. Their father told me signalling in all pit work was safer and more generally used than speech. The holes drilled were varying depth anywhere from an eighteen inch one to straightening off an unevenness of the face up to the long six feet.

There were four length drills, eighteen inches – three feet, four feet and six feet which meant four changes of drill each time a six feet hole was needed.

I should mention here, that when Sam was firing the holes in our second firing, the ones left over from a previous blast, I had my first sight of mine traffic, to and from the actual face workings. On our way in that morning I had seen the three mile endless ropeway, non-stop, empties going in, full’uns coming out, on what was practically a duel carriage way, also the self acting inclines, where the weight of the full tubs, at one end of the rope, going down the bank, brought up the same numbers of empty ones. On the other end to the bank head, easily controlled by a brake strap round the drum, the long Carlin How Bank with its main and tail ropes, ran from its engine house on the surface at the Pit-top, but this was the first stage in the movement of the newly won ironstone, on its long journey to the Teesside furnace, standing where Sam had told me and stop anyone going by me, I heard in the distance a rumbling like thunder and coming ever nearer, changing in tone to a bumping and clattering, then two lights coming nearer, a trotting horse and two pair of legs, I called out ‘fire’ a sprag went into a wheel of the first tub, bump, bump, bump and all was still. The driver, the bigger lad or young man, I could call him, fag in mouth (woodbines five for a penny) left the smaller lad at the horses head and came running along, stopped, looked hard at me and said in one sentence "Hullo, new lad, firing, where, are yer lit up Sammy, can we go by, me men waiting". He ran back past me to the horse and tubs, drew the sprag from the wheel and banging on the iron tub, drum fashion (Howay Kit), way they went, the horse, eighty empty tubs, two lads broken into a steady trot past me, he raised the iron sprag in salute and unerringly threw it into the spokes of the last wheel which tighten all the couplings, making a firm pull, jumped on the back bumper, raised his hand “see yer again kid, so long Sam” his action reminded me, in spragging the wheel of a chap showing off when he’d got a treble at darts. Oh when I saw them coming along and called fire, I raised my lamp up and down, up and down, for a stop. Swinging sideways meant all clear. All this happened nothing more, than I should think from three to five minutes. When I spoke to Sam of the young fellows attitude he simply said “one of the best David, all that matters to Ted is that his fillers don’t have to wait for wagons” I was with Sam for about six months, during which time I was sensibly told much, aye, much of mining for which I already felt a great interest.

Once when a Mister Hudson, under manager was making his periodical visit, and sat talking to Sam, he asked Sammy, how I was shaping, Sam must have answered satisfactorily, for Mister Hudson said I shall probably be taking him from you in a week or two. I remember Sammy saying “I want him looking after Bob, I promised his Father” at this Hudson broke into “come here lad. I won’t bite, tho they tell me I’ve an awful bark, why didn’t your father take you to Morrison’s (the other Brotton mine) with him, there’s nothing your Dad could not have told you about this work” Sam said “His father wants him to make good, without any sheltering.

“Yes, Yes have ago at everything, everything, experience builds fine solid characters, so long” Bobs Hudson’s advice sunk deep), and away he went.

000420

Off to War

It was not long however before I was to meet up with him again. Some few weeks later, the man who opened the cage gate at the shaft bottom said “ you’re to call at’t bosses cabin Sammy” “come on David” Sam said “we’ll have to see what’s on”. Half way to the stables quite a few men and boys were sitting about and later when I asked him what they did, he told me they were travellers, filling in for absentees, and needed to be capable as jacks of all trades, no mine could carry on without its travellers. When he came out from seeing Mister Hudson and got on our journey he said “well it’s the parting of the ways lad, he’s got a new boy for me and instead of coming with me on Monday morning you’ve got to call at that cabin where we’ve just seen Bob (Hudson, under manager) “what he’ll send you to I don’t know but you’ve worked well with me, carry on like that and you’ll get on alright”.

On the following Monday morning, I felt a bit lost going down among other men and without Sam, who for rather more than six months I had followed like a dog, but really I had enjoyed every minute of my earliest experiences of Ironstone Mining. When I arrived at the bosses cabin on the Monday morning there seemed even more people about than had been there on the Saturday, and to my great surprise three lads who had been sitting on a heap of timber all got up calling ‘David, are you going with us?’ I replied I didn’t know what I was going to do , I’d just left stemming- carrying last week and to wait here for orders.

Jack Pennock who I knew had been working in the joiners shop on the surface said you may be going with us David, we were told to wait here until another boy and some men arrived. Just then Tom Maughan, overman, came out and called “come on you lads” and took up the opposite side of the shaft. From my previous travelling road. You are going to work with some bricklayers he said. The other two lads Urban Wright and Frank Allen had been surface workers in the blacksmith’s shop.

When I was an errand boy at Langman’s in Station Street, Saltburn, Frank and Urban were both at Gray Poulter’s across the road. Jack was a delivery boy at the laundry, pony and van in those days. The over man conducted us through a narrow passage, just beyond the number two shaft, through two heavy doors, which when opened nearly drove us back with the strong air current. At the top of number two shaft, about a hundred yards away from number one, stood a large engine house, containing the hydraulic pumps for drawing water out of the mine and emptying it into a steam where it eventually reached the sea. The other purpose of this large building, was to house a large rotary fan, which when working drew the stale air from the pit, thus causing a large vacuum, into which rushed fresh air, down number one shaft, Carlin How shaft, Craig Hall shaft and other minor borings, known as staple shafts, so called as the only means of using them was by iron ladders affixed to the walls. A large cavity made by taking up the stone below the actual seam for a length of a pillar, about forty yards and to a depth of about six feet and looking very much like a large swimming bath was were we were to work for rather more then the next six months. When completed with four feet six thick brick walls, sided and ends closed, it formed an underground reservoir, known in the pit terms as a water standage, into which water from districts all over the mine collected and was taken up the shaft by the big pumps of which I have spoken and so disposed of.

Lumpsey was a well ventilated and well drained mine, the mortar for bricking was mixed by pug-mill on the surface and sent down in the tubs used for carrying ironstone. We boys had to empty it out on to boards laid on the floor, keep it usable by constant turning with our shovels and barrow tit to the four brickies employed when one yelled ‘mortar’. It was heavy work for us youngsters, just away from school and when I mentioned it to one of the bricklayers (from Saltburn) that I knew said “ Well it’ll make men of you and we don’t want keeping waiting, it’s a contract job and you’ll get a rise in wages” We did from seven and sixpence to nine shillings for a six day week of forty six hours.

How-ever – contract finished – water rushing into the standage on all sides, big pump above sucking away greedily, water going down the Saltburn beck (past the bottom of our garden) and to us boys at that time, a wonderful tip of ten shillings each, in the shape of a golden half sovereign and another chapter of my life closed…following that I moved about on various jobs. Leading horses for the drivers, (half-crown lads) so called for their daily rate of pay. Next step up he became a (two and niner) two shillings and nine pence per day. A driver off work, I took his horse , I did the same work he had been doing, but I didn’t get his rate of pay, just my one and six, a whole shilling less for the self same job. When I spoke to my father of the unfairness of it, I didn’t get any sympathy. He just said “don’t you start getting too big for your boots or you’ll be finding yourself out of work!”. This expression from my dad got my back up more or less and I wondered do we have to just go through a working life and take what you are paid and never query it.

I was only about fifteen and a half at the time and yet felt there was something wrong about it. I continued for some three or four months at many varied jobs. Occasionally I was on one or two jobs where a lad or young man was off sick or injured which lasted a few weeks or more and it was on one of these, running the number three bank ( a self acting incline) where the weight of the full tubs going down drew the empties up, that I made up my mind that it was all wrong and the time to speak. Jim King, the bank man whose place I was satisfactorily filling, was paid two and nine a day and I was still getting my one and six. My mind made up, on going out of the pit I went to the office and asked to see the Manager (Mister John Chapman) “Well David, what is it , some kind of trouble” “not exactly” I said and passed on my opinion of more than one aspect of the unfairness of the pay pricing. He had a hearty laugh and said “What do you expect me to do about it” “ You’re the manager” I said “you should be able to alter it” “I’m afraid I can’t” he said.

The outcome was that I asked for my money, fifteen shillings for a week and four days, went down to Skinningrove pit and started next day, mans work, timbering, doubled my rate of pay and was there till I went to France to War – in August 1914.